Juneteenth is a celebration marking an end to slavery in the United States. Though Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, very few people were immediately freed. It proclaimed that “all persons held as slaves” within the rebellious states “are, and henceforward shall be free.” But the nation was in the midst of Civil War and, of course, “rebellious states” were in no mood to pay heed to Lincoln’s order. So, although the Proclamation marked an important shift in federal policy, millions of African Americans had to wait until the Confederacy was defeated before they could begin lives as freedmen. Hundreds of thousands of blacks did take advantage of the new opportunity to take up arms fighting to end slavery as members of the United States Colored Troops (USCT) and to flee enslavement as “self-emancipators” but their efforts were not sufficient to end the “horrible institution” before the war’s end.

Once Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered to Union General Ulysses S. Grant on April 9, 1865, Congress pressed to ratify the 13th Amendment, which legislated that no one could be held in involuntary servitude, except as punishment for a crime. With this, African Americans could begin to experience some degree of human rights. They were certainly not equal with regards to opportunity or law, but they were no longer regarded as property. But it took news of this new beginning a long while to travel. Indeed, troops continued fight until June, a full two months after the war was over. Slave holders were loathe to respect the change in law. And enslaved people, often isolated and illiterate, had limited access to information. A full two and a half years after the Emancipation Proclamation and two long months after Richmond fell, the last enslaved African Americans in Texas were pronounced free people. That momentous date, June 19, 1865, has been proclaimed Juneteenth and celebrated annually ever since.

Big Bethel Emancipation Day program, 1906. Courtesy of Auburn Avenue Research Library.

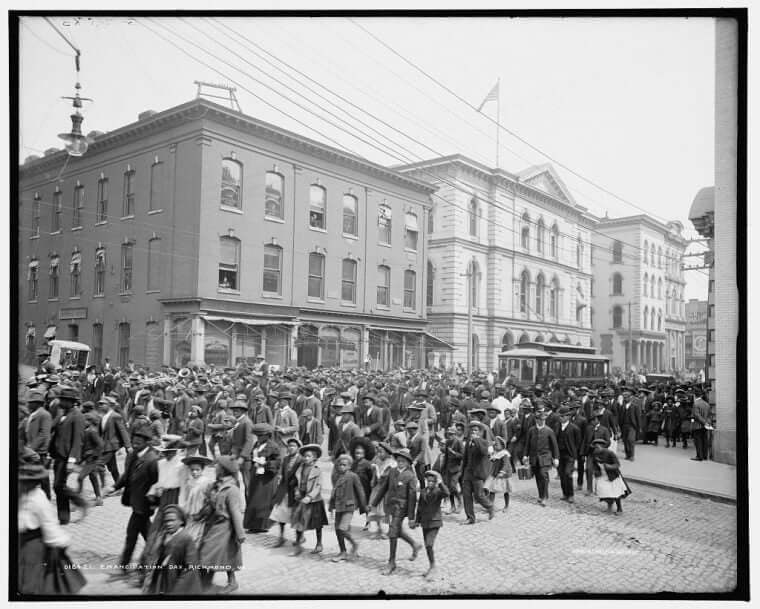

Given the state’s large black population, the scope of their celebrations, and the range of their national migrations, it’s not surprising that this Texas-specific event gained national preeminence. Still, it is important to note that African Americans celebrated their freedom on many dates across the nation. For more than 150 years, for example, South Carolinians and Georgians, have held Emancipation Day programs on January 1, in honor of the Emancipation Proclamation. Big Bethel AME Church in Atlanta hosted a major event featuring oratorical contests, plays, music, and a shared meal. In many local communities, parades celebrated the service of Union troops, especially members of the USCT, and picnics showed African Americans claiming public spaces that they usually were forbidden to use.

Juneteenth and Emancipation Day festivities commemorated the struggles of people who had been enslaved. It was a way for their communities, and later their descendants, to honor their sacrifices and affirm their general hopes for a better future. It was also, however, a way for them to assert their humanity and rights to full citizenship. In times when it was illegal in many places for African Americans to even congregate in large numbers, these celebrations were an act of defiance. In Southern towns where Confederate defeat was deeply resented by white locals, parades by uniformed members of the USCT spoke to blacks’ joy about—and participation in—Union victory.

As the Civil War became more distant, Juneteenth and Emancipation Day programs focused on highlighting black achievement, showcasing rhetorical skill, fine arts accomplishments, and the progress of institutions like churches and schools. In 1957, when Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. addressed Atlantans at the NAACP Emancipation Day rally, he chose the subject “Facing the Challenge of a New Age.” His speech, broadcast live on the popular radio station WERD, was a rallying call for Civil Rights activism.

Unfortunately, as Southern African Americans migrated out of the region, many of their traditions were lost. Juneteenth and Emancipation Day seemed less urgent to the shifting community and the events grew smaller. But they never ceased entirely and Black Studies cultural programs in the 1970s intentionally pressed to recover these customs. Now, we no longer have all of the nuanced regional diversity that emerged in 1865, but we’ve recovered a rich, powerful, exciting, and fun-filled practice of celebrating the end of human enslavement in the United States.